- What is a pay for performance model?

- Pay for performance examples

- How common is it for companies to use a pay for performance model?

- The pros of pay for performance

- The cons of pay for performance

- How to implement a pay for performance model effectively

- So, should you implement a pay for performance model, or not?

Pay for performance is one of the most debated topics we’ve come across amongst People and Reward Leaders.

In a pay for performance model, compensation reviews and performance reviews are linked and high-performing employees are rewarded with a salary increase (or ‘merit increase’).

This provides a structure for financially incentivising high performance, by rewarding top performing employees for their contributions.

But, when performance is the main factor in salary adjustments, it can lead to inconsistencies and inequities in compensation across all employees. Plus, some evidence suggests that increased compensation may not be an effective method for improving employee motivation and performance in the long-term.

There are valid arguments on both sides of the debate – and that’s what this blog post explores.

Subscribe to our newsletter for monthly insights from Ravio's compensation dataset and network of Rewards experts 📩

What is a pay for performance model?

Pay for performance is a compensation model where an employee's salary is directly linked to their performance. The aim is twofold: improve performance and productivity by incentivising performance, and recognise and reward a company's top performers to support their retention.

Pay for performance examples

Pay for performance refers to any scheme that aligns employee compensation with measurable performance achievements – including merit cycles as well as other schemes such as sales incentive plans.

Examples of pay for performance programmes include:

- Merit increases during a compensation review

- Non-salary pay for performance levers during compensation reviews – such as performance bonuses or equity refreshers

- Incentive plans

- Profit-sharing bonuses.

Merit increases during a compensation review

A merit increase is a salary increase granted to an employee specifically to reward them for high performance.

In a pay for performance model, compensation reviews become 'merit cycles' – used primarily to recognise and reward employee performance. Performance evaluations are conducted, with the resulting performance ratings used as a key input to decide salary increases, with employees who exceed expectations rewarded through a higher salary increase.

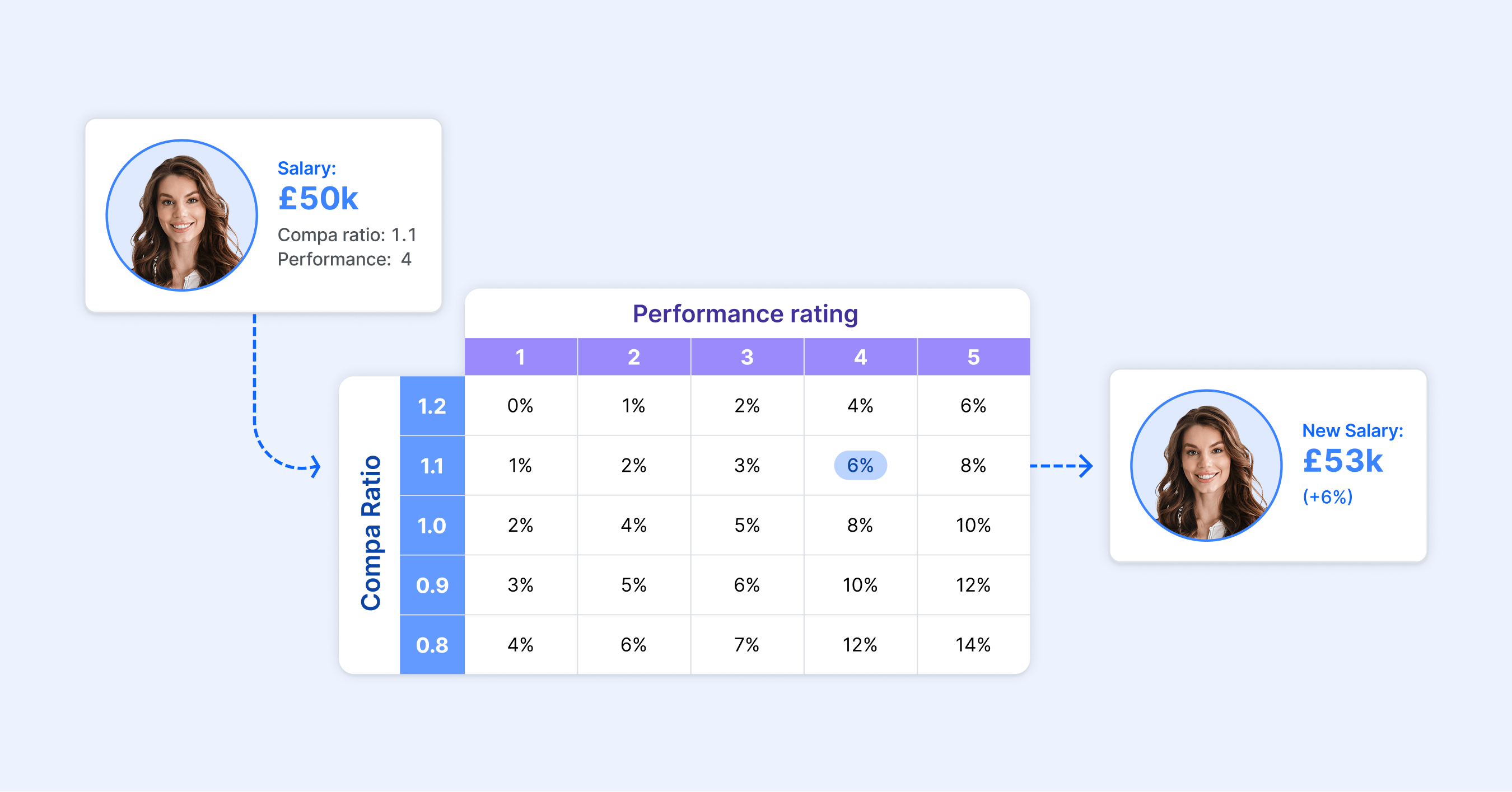

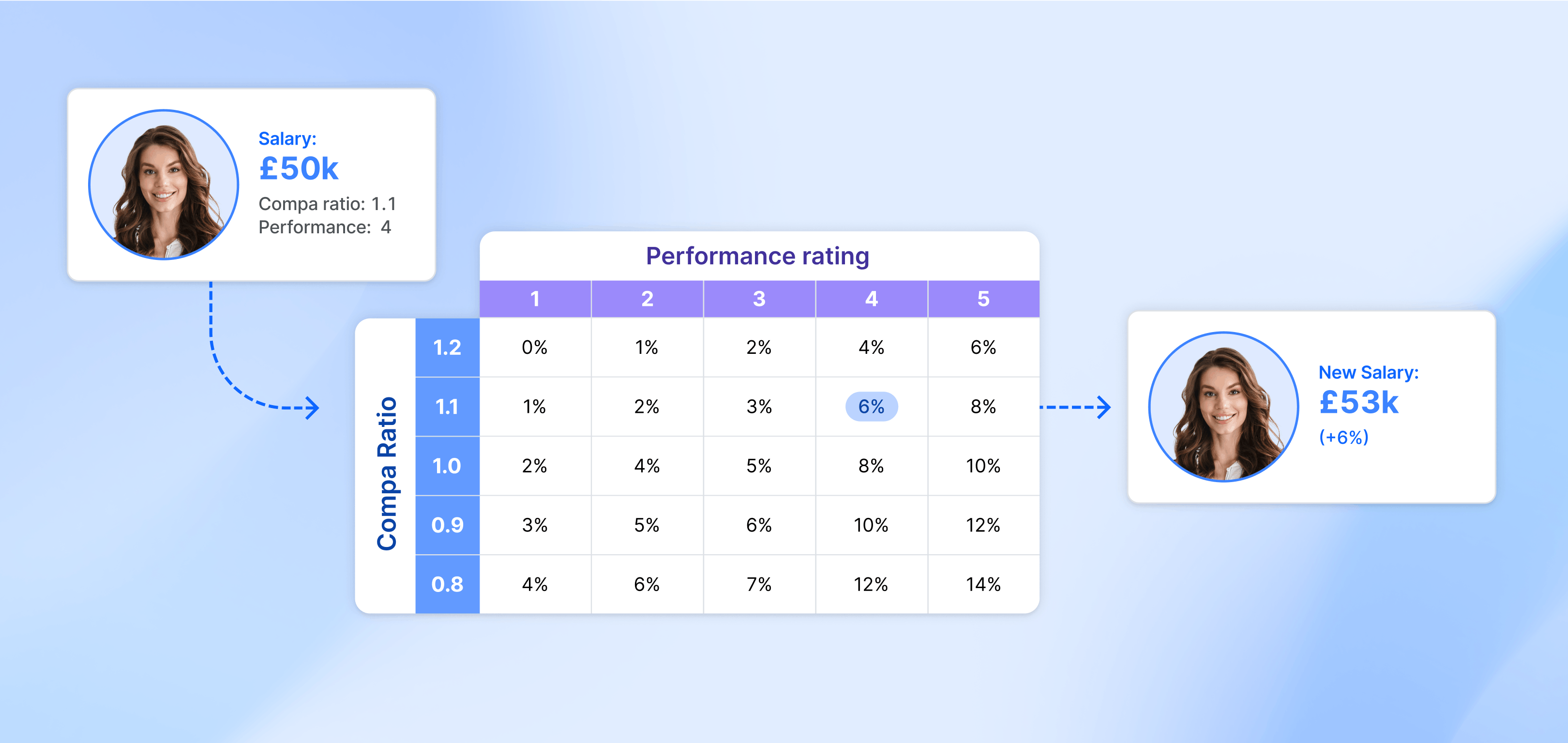

Some companies use a merit matrix to ensure that salary band position is also included as a factor in the merit increases, to account for team wide consistency and pay equity.

Non-salary pay for performance levers during compensation reviews

Some companies opt to focus salary adjustments on factors like market changes or employee progression (promotion increases) – and use other levers to reward performance.

The primary reason for this is to avoid compounding inconsistencies in base salaries, which can cause pay equity issues later down the line – especially if there's any element of bias or subjectivity in the way that performance is evaluated. Using other levers can also help with payroll costs by avoiding performance increases being baked into ongoing base salary costs.

Those other pay for performance levers include:

- Bonuses. Performance bonuses can be granted to employees who get high performance ratings, or achieve pre-defined goals or targets. This might be an ongoing scheme, or it could be one-off spot bonuses.

- Equity refreshers. Additional equity compensation is granted to high-performing employees, rather than a cash bonus. Equity can be particularly valuable as a long-term incentive for retention, due to the nature of vesting schedules.

- Employee recognition programmes that acknowledge and praise employees for their contributions. It could be as simple as a 'shoutouts' channel in the company Slack, or it could be a more formal programme such as a point-scoring awards scheme with team nominations.

- Accelerated promotion pathways. High performing employees are likely to be progressing much more quickly within their role, and this should be reflected through accelerated promotion pathways. Working with their line manager to implement a performance plan that helps them progress to the next job level, and achieve a promotion pay increase, can be particularly valuable for employees.

- Additional benefits. Rewarding high performing employees with desirable employee benefits such as learning and development budget, or enhanced flexible working (e.g. a 4 day workweek at full salary) can be a powerful pay for performance lever.

“The beauty of compensation is that there are so many levers to pull to reward employee contributions – and different levers work for different employees.”

Founder of Oliver Reward Consulting

Incentive plans

Incentive plans are used to motivate employees to achieve (or exceed) defined targets, or to implement certain behaviours – and so are a great example of a pay for performance model.

Examples include:

- Sales incentive plans: used to motivate sales teams to hit targets, such as a number of deals or an amount of revenue – this could be through a commission structure, performance bonuses, or non-cash incentive like extra days off or prizes like a paid trip abroad.

- Short-term incentive plans: used to reward employees for achieving specific performance metrics within a short time period (usually one year or less) – most commonly cash bonuses are used as the incentive.

- Long-term incentive plans: used to incentivise employee performance and retention over a long period of time, usually using deferred compensation such as additional equity compensation which is only granted after a set period of time e.g. 3 years.

Profit-sharing bonuses

Profit-sharing bonuses are used to link company success with employee compensation, distributing a portion of the company's profits to employees if the company achieves defined goals or targets. Profit-sharing can be an effective way to incentivise employees by building a heightened connection between individual work and business objectives.

Profit-sharing is particularly common for values-led companies like Buffer, who want to ensure that employees share in the success of the company.

How common is it for companies to use a pay for performance model?

Data from Ravio's compensation review report shows that 86% of companies include performance-based adjustments in their pay review – making it a near-universal part of the process.

The research found that there isn't much variance in this as companies scale, with pay for performance common across all company sizes – but even more likely to be included in pay reviews at large enterprises with 1000+ employees.

Of the companies that include performance-based adjustments in their pay review, the overwhelming majority (93%) use base salary increases to reward performance – and this stays broadly consistent across all company sizes.

Larger companies typically complement salary increases with additional levers, with performance bonuses much more common at mid-size and large companies (60% at 500-1000 employees and 62% at 1000+ vs 49% overall), as well as equity refreshers (47% and 58% respectively vs 40% overall).

Smaller companies are more likely to get creative with employee benefits. Companies under 100 employees are twice as likely to offer additional flexible working (24% vs 16% overall) and learning & development budgets (29% vs 14% overall) as performance rewards.

This likely reflects increased budgets at larger companies, but could also suggest that smaller companies are able to be more agile and flexible in responding to what employees want from total rewards packages – particularly the growing value of flexible working opportunities.

63% of companies that use salary increases to reward performance use a merit matrix approach wherein performance ratings are combined with salary band position – a way to maintain systematic fairness whilst rewarding performance.

This becomes more common as the size of the company increases, reflecting the growing importance of consistency and pay equity for larger companies.

Examples: How different companies reward performance during pay reviews

Finom: Combining performance and market data for pay increases (500-1000 HC)

Finom prioritises building a high performance culture to meet ambitious company goals, so recognising top performers through salary increases is central to their compensation reviews. They've also introduced an equity scheme where management can nominate a handful of outstanding employees for additional equity compensation each year. However, salary increases are also informed by up-to-date market data for each location, balancing performance recognition with market competitiveness to attract and retain talent.

Pipedrive: Keeping performance and pay separate (1,000+ HC)

Pipedrive separates salary reviews from performance, focusing compensation reviews on market competitiveness, pay equity, and employee progression. Performance is still recognised, but through annual bonuses and career development opportunities instead of through salary increases. This separation is to avoid consolidating performance increases into base salary forever, where it can cause ongoing and compounding issues with fairness and consistency across the organisation.

CrowdBuilding: Mission-aligned progression paths (<100 HC)

CrowdBuilding rewards performance through structured progression rather than traditional merit increases. Employees advance through four skills-based sublevels (learning, established, thriving, stellar) with pay increases reflecting their inrole development. Additionally, employees can earn up to 10% extra for demonstrating expertise related to the mission of affordable housing – either when joining with existing industry knowledge or by developing this expertise over time. This dual system ensures pay reflects both professional growth and mission-critical knowledge.

The pros of pay for performance

The advantages of using a pay for performance model for salary adjustments all centre around the importance of recognising and rewarding employees and compensation as one vital lever in this.

The three main pros are:

- Supports the retention of top talent

- Increases employee motivation and improves output

- Improves strategic alignment.

1. Pay for performance supports the retention of top talent

Recognising and rewarding high performance through financial gain can be an effective incentive to keep hold of your best employees.

It’s typical for there to be a handful of high-performing employees who have a disproportionately large impact on company success. Retaining these employees becomes a business priority, and a merit increase that increases their base salary is one way of achieving this. Ensuring their pay reflects their heightened business impact means these top employees are less likely to be tempted to leave by a role with a higher compensation package at another company.

2. Pay for performance improves employee motivation and output

Linking salary increases with performance can be an effective way to boost overall employee motivation and morale to meet company goals or revenue targets – improving employee output and, therefore, company performance.

There are many research studies exploring this. A 2020 study, for instance, switched employees from fixed wages to a performance-based pay model, and measured the impact on a routine task. They found that performance-based pay increased the number of pages typed by employees by 10%.

However, it’s also worth noting that there are many research studies that have the opposite result, finding that merit pay for performance can be detrimental to overall employee motivation and performance – we’ll explore this in the next section.

3. Pay for performance improves strategic alignment

Linking compensation reviews with performance means being able to evaluate what ‘high performance’ looks like. That typically includes providing clarity on the company’s strategic direction and goals, and how the priorities of each team and individual support with working towards those goals.

If this is done effectively, it creates alignment between the strategic direction of the business and the day-to-day work of the team, rewarding those employees who are clearly contributing towards business goals.

This strategic alignment brings focus and unity to the entire team, which can only ever be a positive for company performance.

The cons of pay for performance

Whilst the pay for performance model can be a great way to incentivise and reward employees, there are also some potential pitfalls which can reduce the effectiveness of the approach.

The main pitfalls of pay for performance are:

- Reliance on subjective performance reviews

- Encouraging an individualistic and competitive culture

- Encouraging short-term thinking

- Increase employee stress levels

- Increase the risk of salary compression (if performance increases are the only form of compensation adjustment).

1. Pay for performance relies on subjective performance reviews

There are many ways to review performance but all are reliant on the feedback, perspectives, and interpretations of ‘performance’ by colleagues and, especially, managers.

In fact, a study by Mercer found that a huge 90% of HR leaders feel that performance reviews do not yield accurate insights on employee performance.

This means that subjectivity and human bias is always involved in the process to an extent – there are ways to reduce the impact of bias (discussed later in this article), but it’s very difficult to remove entirely.

Bias inevitably leads to pay equity issues.

Visibility bias (also known as presence bias or proximity bias), for instance, typically impacts women more than men as they are more likely to have time off for parental leave and also more likely to embrace remote working. Plus, men are more likely to feel confident in asking for a salary increase – those who visibly shout the loudest are often the ones rewarded for ‘performance’.

Ultimately, linking pay and performance can reduce the fairness of compensation reviews by introducing subjectivity and inconsistency into compensation decisions.

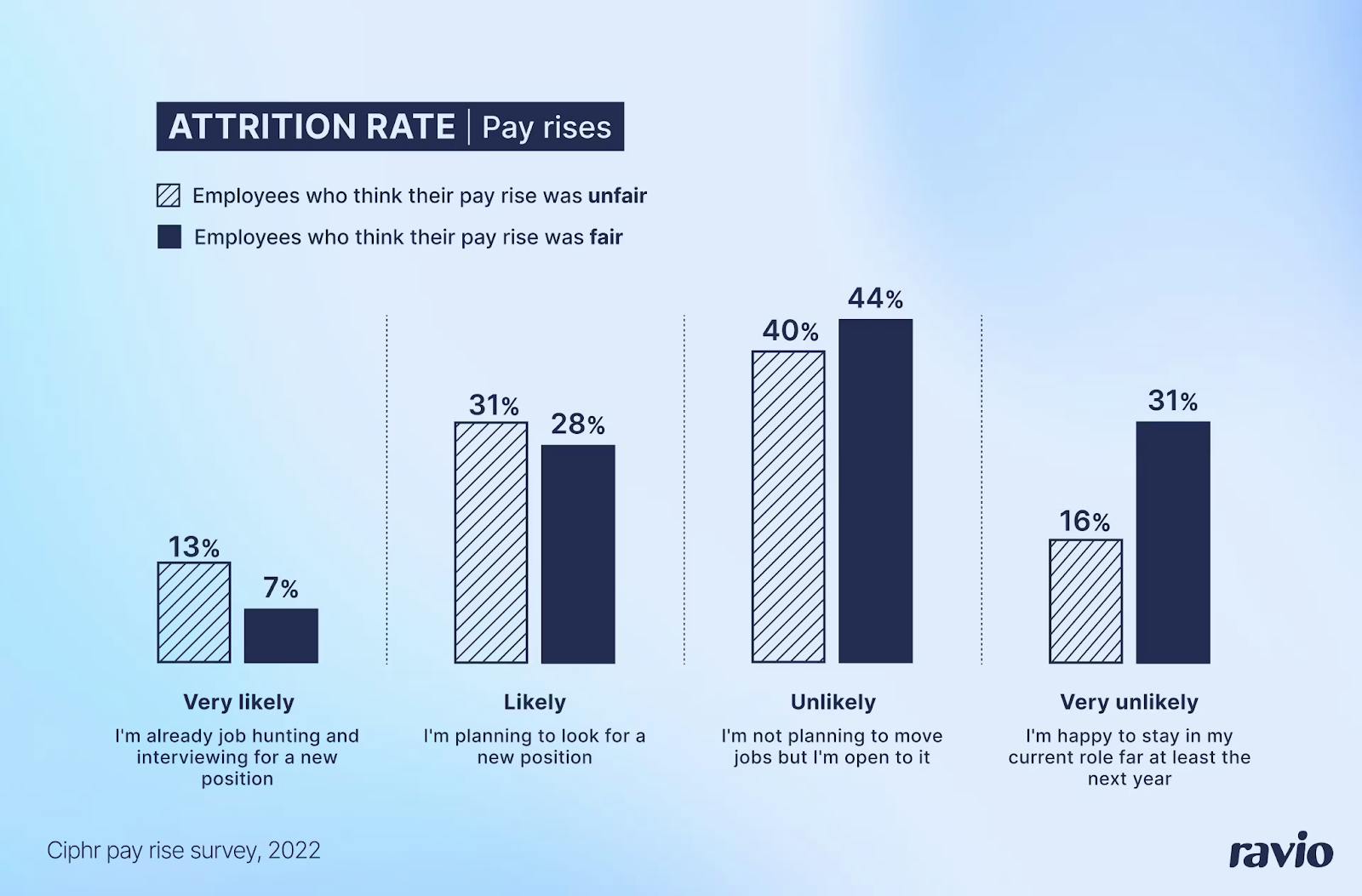

Beyond the pay equity problem, when compensation decisions feel unfair, it can heighten attrition risk. Employees who feel they have worked hard and are deserving of a pay increase will feel frustrated.

Research backs this up: Ciphr surveyed employees about their last pay rise and found that 44% of employees who think their last compensation review was unfair and not reflective of their job performance, are likely or very likely to move roles in the next 12 months. This compares to 25% of those who see their last pay rise as fair.

2. Pay for performance can encourage an individualistic and competitive culture

Rewarding employees for performance can lead to an individualistic culture where individual wins are favoured over teamwork and collaboration – a ‘me-first’ mentality.

“In contexts where teamwork and employee cooperation are important, the introduction of high-powered incentives (such as individual performance-related pay) may induce excessive competition and reduce employee willingness to cooperate.”

This is especially true if there is a limited pool for salary increases based on performance, because it encourages a competitive environment with all employees wanting to gain a slice of that limited pool.

One way to counteract this is to set team targets rather than individual KPIs, so that teams are rewarded for overall performance.

3. Pay for performance can encourage short-term thinking

Performance reviews typically happen once a year, and employees are well aware when they’re happening because they’re involved in feedback requests and performance conversations.

If employees know that they need to meet certain requirements or hit certain goals in order to achieve a high performance rating, they might be incentivised to game the system e.g. explore low-quality shortcuts that could help them reach those performance indicators in time to achieve their pay raise.

Those shortcuts could cause negative consequences for the business later down the line.

Plus, it may actually lead to reduced performance in the long-term, with a short burst of effort in the run up to the performance and compensation review, but a lack of motivation or incentive to work hard for the rest of the year.

“Providing incentives based on extrinsic motivation may offset an inner willingness to work or perform certain tasks and actually reduce output.”

4. Pay for performance can increase employee stress levels

Conversations about pay and performance aren’t easy for anyone involved.

For employees, there’s often a lot of anxiety involved when performance and compensation are linked. They want that pay increase (we all do!) but there’s a lot of stress involved in putting yourself forward and proving your worth.

Studies suggest that this heightened stress is detrimental for performance levels, offsetting the positive impacts of motivation that pay for performance can induce.

One survey of 300,000 Danish employees even found that employees are 5.7% more likely to require antidepressants in companies that use a pay for performance model.

It really depends on the employee – for some employees working towards a performance pay increase is a positive experience, for others it’s negative.

For this reason, it’s important to understand how pay for performance impacts your specific team before deciding whether or not it’s the right approach for you.

“Just like two sides of a coin, pay for performance can be both a stressor and a motivator for employees.”

On top of this, it’s stressful for managers too. Managers have to handle difficult conversations with their team members about a very personal topic area. The subjective nature of performance ratings makes it especially challenging to explain and rationalise decisions to employees.

And it can also be very frustrating for People and Reward Leaders, because those difficult conversations and subjective outcomes often lead managers to blame the process or to not explain the rationale behind pay increases. This increases employee frustration, and reflects poorly on the People Team for no good reason.

5. Pay for performance can increase the risk of salary compression

If performance is the only factor in the compensation review, with no market adjustments made, then salary compression is a real risk.

Salary compression is when new employees receive a higher base salary than existing employees for performing equal work (or work of equal value).

This happens because new employees have their new hire salary offer benchmarked against up-to-date salary benchmarking data – whereas existing employee salaries are based on out-of-date data from when they were initially hired.

The talent and compensation market moves quickly so it’s important to review compensation against up-to-date benchmarks, at the very least once per year during the compensation review.

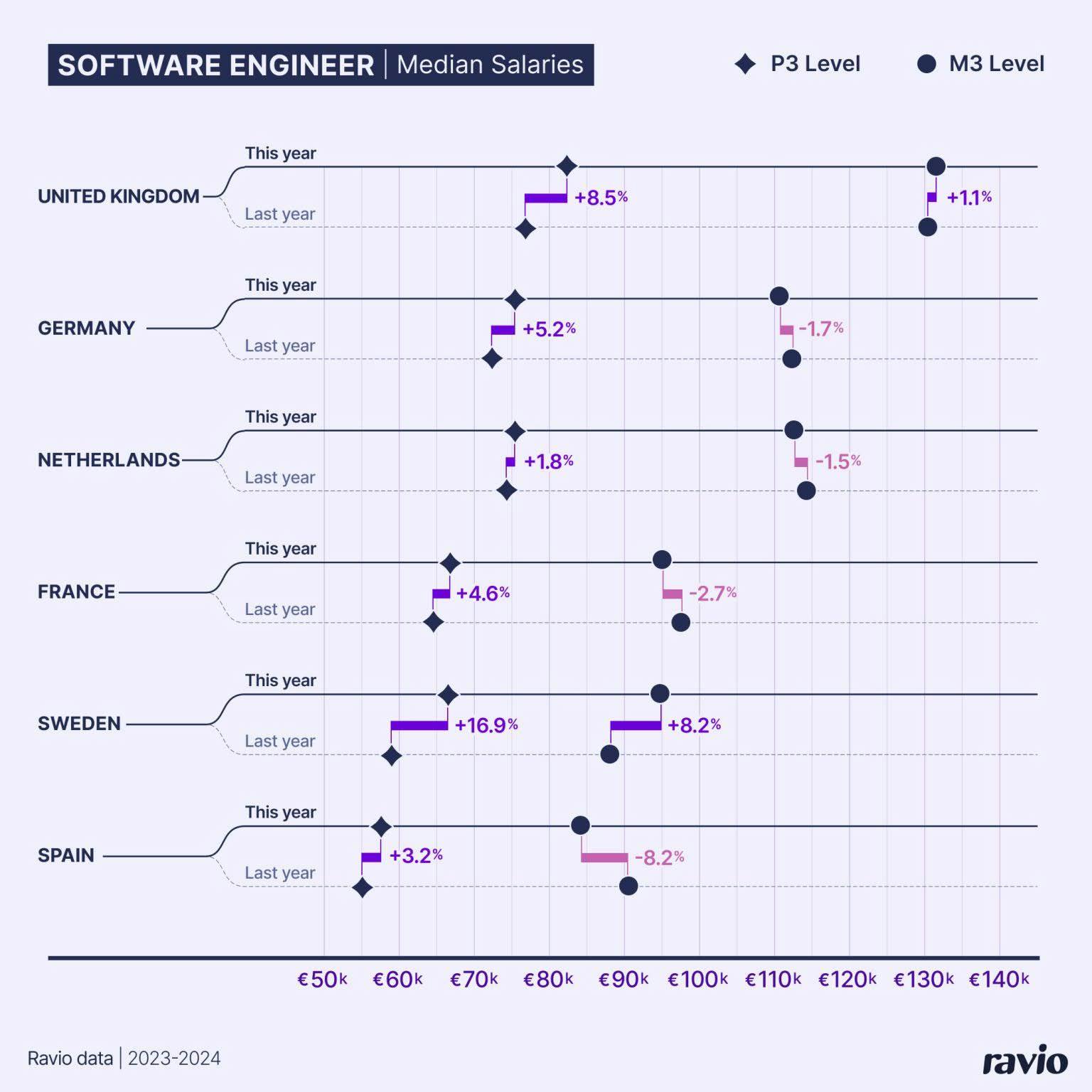

To give just one example to illustrate this point, we can see from Ravio’s latest Compensation Trends report that software engineering salaries in Europe have been volatile in just the past year alone (2023-4) – with significant increases in competitive pay at the P3 level, and decreases at the M3 level. If the timeframe was extended, we’d see even more change in competitive salaries.

💡 Why Pipedrive stopped adjusting base salaries for top-performers as they scaled

Pipedrive is a sales CRM and pipeline management tool. Pipedrive was founded in Estonia in 2010, and has since grown into a company with 1,000 employees.

As Pipedrive’s headcount increased, the decision was made to separate salary increases from performance ratings. Instead, Pipedrive shifted to a “market-driven pay” approach, using the compensation review period to bring salaries in line with up-to-date salary benchmarks, whilst also conducting an analysis of compa ratios and internal pay equity. The aim is to ensure that employee pay always remains fair and competitive.

As Tanya Krasnova, Senior Reward and Benefits Manager at Pipedrive, puts it:

“Instead of focusing on past performance, our annual salary review looks ahead, considering skills, experience, and how an employee's pay compares to the market to stay competitive.”

This focus on eliminating internal pay equity issues is becoming increasingly important “given the growing regulatory scrutiny” as new laws like the EU Pay Transparency Directive approach – Pipedrive’s approach ensures that company-wide consistency is maintained.

Pipedrive does still use the ‘pay for performance’ model though, just not for base salaries. Instead, performance is rewarded through an annual bonus plan and commission scheme.

“By paying for past performance you are paying for that forever as it is consolidated into base, whereas by paying for performance via bonus, this is just for that year. This leads to more fairness and consistency.”

High-performers are also encouraged to take on additional responsibilities, train on new skills, or test out other job roles outside of their discipline – helping them to reach the next level of promotion more quickly. Plus, a recognition platform means that employee achievements are constantly being highlighted.

As well as ensuring fair and competitive pay, the shift has also been great for employee communication: “For employees, it means they don’t have to rely solely on annual reviews for recognition – they know they can expect fair and consistent salary reviews along with other growth opportunities.”

How to implement a pay for performance model effectively

As we’ve seen, there are several potential issues that can arise when combining pay and performance, with particular worries including a negative impact on pay equity and company culture.

That doesn’t mean that they can never work – whatever approach you decide for compensation adjustments and performance, the success always lies in how you implement that approach within your specific company.

We spoke with Rewards experts Figen Zaim, Global Rewards Consultant and Founder of Olivier Rewards Consulting, and Rob Green, Global Rewards Consultant who is Founder of Darwin Total Rewards, and an Associate within the MCR Consulting group, about how to implement a pay for performance model effectively.

The top pieces of advice that came up in conversation were as follows:

- Clear inputs that reward the right business outcomes

- Use a merit matrix to incorporate market adjustments

- Focus on long-term development not short-term performance

- Clear guidance for managers

- Explain the rationale to employees, supported with 360 feedback

- Incorporate other methods of reward and recognition too.

1. Clear inputs that reward the right business outcomes

To reduce the role of subjectivity in merit increases, it’s vital that the inputs that determine performance ratings are as objective as possible.

Figen advises that to minimise personal judgement there must be “clear reasons behind the decisions being made, and consistency in using those reasons”.

That means ensuring that there is a defined set of performance factors which, combined, determine an employee’s performance rating. These factors might include hard skills and technical abilities required for certain job roles or levels, as well as soft skills like creativity, collaboration, or flexibility.

Rob points out that when defining these factors it’s important to include detail on ‘how’ you would expect employees to meet expectations for that factor within their role in the framework of the organisation’s overall values and culture. This will improve the objectivity of the assessment by giving an anchor example for managers to make a fair comparison to. “If the rating is on ‘what’ and ‘how’ then it’s healthy. If it’s just on ‘what’, then it can lead to inconsistencies across the organisation.”

In terms of which factors to include, for Figen, this should always “be led by your company culture, which means always going back to what aligns with the company's specific purpose and values.” There will typically be certain behaviours and actions that it’s important for a company to motivate and reward in order to maintain the right culture and make progress towards the company’s overarching mission.

2. Use a merit matrix to incorporate market adjustments

We’ve also seen that inconsistencies, pay inequities, and salary compression can arise when performance is the only factor used to inform salary adjustments.

For this reason, we’d always recommend that market adjustments are incorporated into the salary increase too.

Merit matrixes are one way to do this: an approach that combines an analysis of the market competitiveness of an employee’s current salary with their performance rating.

All employees who receive a high performance rating are rewarded, but in theory those who are already high in their salary band will receive a lower salary increase than those who are currently at the lower end of their salary band. This makes it easier to maintain pay equity and avoid salary band outliers, whilst still rewarding performance. Rob highlights that “discretion should also always be part of the final decision making process, to enable the business to own the process and communication.”

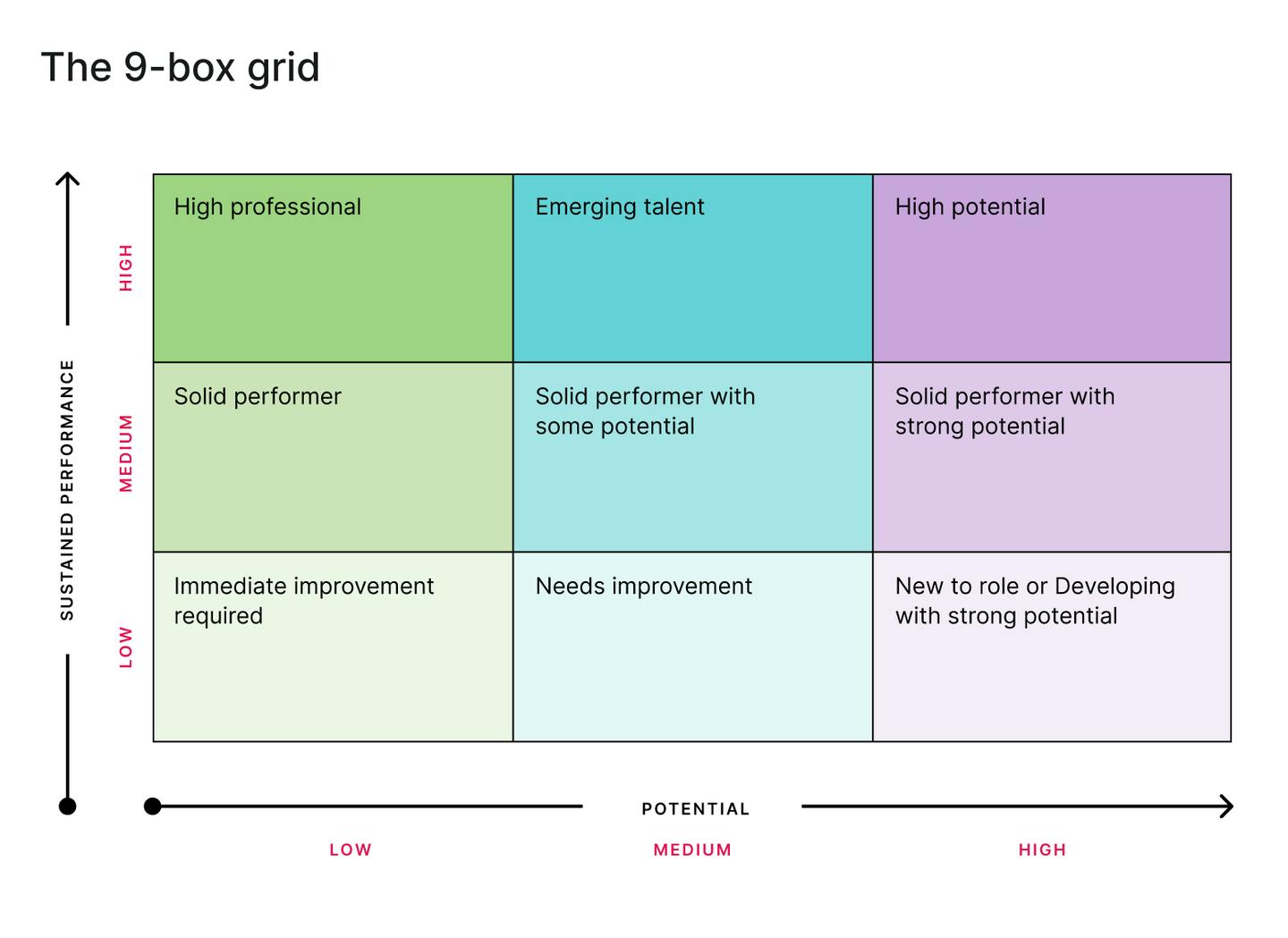

Another method is to use a 9 box grid and overlay this with a compa ratio analysis – “the holy grail” for Rob, as “it demonstrates organisational and leadership maturity when all three elements are working together effectively” (performance ratings, compa ratio, and manager discretion).

The 9 box grid combines current performance ratings with future potential for growth, placing each employee into one of the nine ‘boxes’.

Source: Culture Amp

It helps to mitigate the subjectivity of performance ratings by ensuring clear ratings and also ensures that long-term employee development and retention is a key focus of performance and compensation reviews.

Rob’s recommendation to layer the employee’s current compa ratio on top of their 9 box outcome has a similar effect to the merit matrix, ensuring that their current salary compared to their peers is also taken into consideration. This provides a baseline to then enable any further salary increase discretion, as an organisation may still want to provide higher reward to a box 9 employee who already has a high compa ratio.

3. Focus on long-term development not short-term performance

Many of the cultural issues that can arise when implementing a pay for performance model (competitiveness, individual over team, short-term success thinking, stressful conversations) can be mitigated by ensuring that conversations about performance and compensation are not isolated to a one-time review process.

“The worst thing you can do is to wait for a whole year, and then tell an employee that they’re way off where they need to be to receive a pay increase or promotion – don’t wait to give feedback (whether positive or negative) until the allotted time, do it now”, says Figen.

And Rob agrees too: “There’s nothing worse than surprises, as employees lose confidence and trust in the process and leadership.”

Instead of a panicked run up to an annual review, there should be a robust system of regular feedback and conversations about performance, as well as a programme of education to ensure that employees understand how (and when) decisions are made regarding pay and performance.

This isn’t easy to get right.

One major factor is the reliance on line managers to give this continuous, honest feedback, which often they may shy away from. Rob recommends that People Teams spend time and effort cultivating a “culture of feedback and growth” between managers and their direct reports: “a solid 180 and 360 feedback culture between manager and employee helps to ensure upfront and honest communication about pay and performance throughout the year.”

It also helps to frame performance management within employee development through a defined job architecture and career framework: “there’s no point in doing performance management without development”, says Figen.

As a job architecture specialist, Figen always looks at the big picture that the ultimate aim is to support an employee to gain the competencies and experience needed to progress to the next job level for their role – at which point they will receive a (much higher) promotion pay increase, and the company gains the benefit of retaining a loyal and knowledgeable employee.

“This way, the review conversations become much more constructive, focused on the concrete steps that need to be taken on the path to the next level, whether or not they’ve been taken, and how to take the next steps along.”

Rob also emphasises the importance of job architecture as the foundation to levelling, salary bands, and employee pay. Subsequent career frameworks take time to develop and establish, depending on the sector and type of job, but they are critical to building a culture of growth in organisations.

4. Clear guidance for managers

Mitigating the bias that comes with manager involvement in pay and performance reviews requires clear guidelines for managers to follow.

Part of that comes from clarity on the inputs and factors used to make decisions about compensation adjustments, as we’ve already seen.

Alongside this, Figen recommends also introducing educational sessions for managers at the start of the process to ensure that “decision makers are equipped with the right information”.

Managers should leave these sessions with knowledge of “the reasoning behind compensation adjustments – how we think about performance ratings, compensation adjustments, payroll budgets”, as well as “the consequences for their team if bias does creep into the process.”

For Rob, in addition, “early engagement with leadership to co-design the process, including any budget constraints, and quality calibration sessions towards the end of the process” are key.

These calibration sessions bring key decision-makers (People Team, line managers, leadership team) into one room to align on final performance ratings. This improves objectivity by enabling unbiased open conversations and ensuring consensus is found. The ‘quality’ comes down to “open and free discussions” and “capturing the outcomes in a targeted way through clear ratings”. A second discussion to identify the top-performing employees should follow this, for instance with the 9 box grid approach it’s important for leadership to be aligned on who the box 7, 8, and 9 employees are.

5. Explain the rationale to employees

Ensuring that employees understand how decisions about compensation adjustments are made reduces the stress and anxiety involved in the process, as well as reducing feelings that unfair decisions have been made.

“It needs to be a consistent educational programme” says Rob, “because if the reasoning is explained only in a one-off pay adjustment letter, it’s too late. There are foundational pieces that are important for employees to grasp, like how salary bands work and why paying above the band is unusual. And there are also situational pieces. For instance, if there’s a lot of talk in the media about inflation being at 10% this year, it brings added complexities of educating the organisation about the differences between cost of living versus cost of labour, and what principles the organisation follows on reflecting this in salary adjustments.”

Figen again highlights the role of managers in this.

As well as their role in making performance and development an ongoing discussion, managers are also typically responsible for informing employees about the results of their performance and/or compensation review.

That conversation is crucial for an effective compensation review but, in Figen’s experience, is commonly mishandled: “you’d be surprised at the amount of employees who have told me that they just found a pay rise letter on their desk or saw a notification on HiBob, with no conversation at all.”

The solution is to invest time on training managers on how to have conversations with employees about the outcome of their pay review.

For Figen, this typically includes a group educational session with all managers, resources that are available anytime, and 1-2-1 support for managers who are particularly nervous.

And this is especially important at scale ups: “it’s pretty common for employees to be promoted to manager more quickly than they might otherwise when there’s a period of high growth, which means you can have a lot of inexperienced managers who struggle to handle those conversations properly.”

6. Incorporate other methods of reward and recognition too

As we’ve seen, inconsistencies and inequities in compensation across teams can arise when base salaries are adjusted for performance.

It’s important to remember that base salary increases aren’t the only way to reward and recognise performance – as Figen puts it: “the beauty of compensation is that we have so many different levers to pull to reward people for their contribution”.

Using other ‘compensation levers’ like bonuses, equity refreshers, benefits, as well as non-compensation rewards such as recognition programmes or learning initiatives to support development, can help to relieve the pressure on once-a-year merit increases to reward performance and bring the focus to supporting employee development all year round.

💡 Alternative ways to recognise and reward employee performance

- Performance bonus. Additional pay granted as a one-off on top of base salary as a reward for high performance. Performance bonuses can be a great way to get the best of both worlds: the financial reward is still there, but without causing inconsistencies and inequities in base salary.

- Equity refresh grant. Additional equity granted to an employee who has already received a new hire equity grant at the start of their employment. Like bonuses, this can maintain the financial incentive (and for some employees, equity will be more valuable than cash) whilst mitigating against pay equity issues.

- Gift giving. Awarding physical gifts, gift card, voucher, etc to show employees appreciation for their hard work. It’s more likely for companies to give gifts on an adhoc basis to reward specific efforts, rather than as part of the formal performance or compensation review process.

- Employee recognition programme. Recognising and rewarding individual efforts publicly through programmes like employee of the month, values awards, peer-to-peer nominations. This can be incredibly valuable in creating a positive company culture and work environment.

- Learning and development. Supporting high-performing employees with the training or opportunities they need to meet the competencies required to be promoted to the next job level.

For Figen, “it will do wonders for your company culture” to harness these different methods to recognise employee performance in the way that best suits an individual’s needs and goals – because: “more salary is actually the reward with the shortest possible shelf life”.

It’s more often the case that employees are looking towards their next step. Maybe they have frustrations with their current role or they’re interested in learning a new skill, or they want to experience a new part of the business and see if it could be better suited, or they want to build up their subject expertise. “A salary increase might feel good in the moment, but tomorrow those frustrations will still be there”, says Figen. On the other hand, helping employees with a secondment to a different team, or a budget for training, or pairing them with marketing to help build their personal exposure, provides lasting value.

Again, managers are vital in guiding what this should look like, because they know their team members best and are best placed to have open and honest discussions about what a positive recognition or reward experience would look like for them.

In Figen’s experience, this isn’t the norm. “Most companies feel that promotions (and the pay increases that come with them) are the only way to retain employees, whether they’re actually ready for that next level or not. If a great employee is about to leave, the tendency is ‘panic promote’ – to increase pay or throw in a promotion to stop them from leaving. But by this point, it’s normally too late, and this isn’t what the employee actually wants.” So, it’s well worth doing the work upfront to understand individual employees and find the right levers to pull to support their performance and development throughout their tenure.

💡 How do ‘big tech’ companies approach pay for performance?

The most common approach for compensation amongst big tech or FAANG companies is to lean on equity and cash bonuses to reward performance.

Annual equity refresh grants are typically used as the main vehicle for incentivising employee performance and retention in the long-term.

Cash bonuses are used to reward short-term performance, with an annual bonus based on both employee performance and company performance.

So, should you implement a pay for performance model, or not?

Our view at Ravio is that the priority should always be keeping compensation competitive for all employees, both for fairness and retention.

This means that market adjustments are the crucial part of a compensation review – using up-to-date salary benchmarking data to refresh salary bands (as well as equity and variable if relevant to your compensation strategy) and ensure all employees are still within their band and still being paid fairly for their value against the wider market.

Alongside this, it is still undoubtedly important to recognise and reward performance, especially for the retention of top performing employees.

Therefore, we’d recommend using an approach like a merit matrix which ensures that both market adjustments and merit increases are incorporated into the compensation review process.